Tutorial: How to Reduce Background Haze with Masking

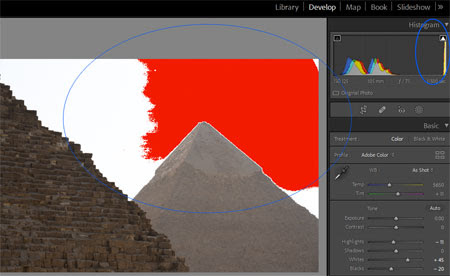

| You may wonder, “Why must I be concerned with photo editing and, in particular, using masks when photo editing?” Here is a very short and direct answer: “99% of the very best photographs that you see around you have been edited using masks… and the other 1% were probably shot on film.” If you want to compete with your fellow photographers, this is a skill that you need to learn. Fortunately, once you understand how it works; it’s not that hard, and, in fact, it adds an entirely new level of photographic fun to your activity. There are many different ways that masks can be applied to your photos. For the sake of this discussion, let’s examine a masking technique that is very common among users of Lightroom and Photoshop. That technique is the “graduated filter”. Perhaps you didn’t even realize that a mask was involved with the graduated filter? The graduated filter is commonly used to bring back some drama to a sky that is overexposed. It does this by allowing edits to affect the sky while everything else is unaffected. This photograph is a classic example of how you can use a mask to improve your photography. |

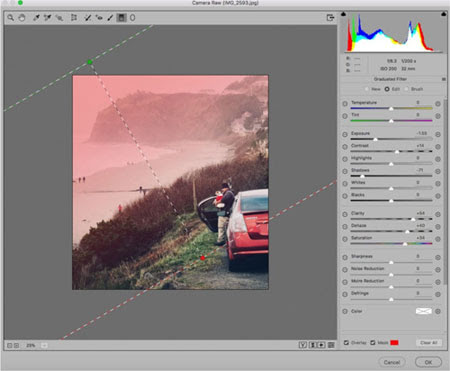

| Due to atmospheric haze, the background is quite washed out compared to the foreground. I am going to show you how the use of a simple mask can even out that exposure level for improved contrast and color from foreground to background. For my example, I’ll be using the ACR (Adobe Camera Raw) window in Photoshop. However, it works exactly the same in Lightroom and most other editing programs. I selected the graduated filter. You can see the darkened “graduated filter icon” at the very top of the screen capture. |

| In this case, my horizon line (from foreground to background) is at an angle. So, I started in the upper left corner and dragged down to the lower right corner. Before dragging the graduated filter across the picture, I checked “overlay” and “mask” in the lower right corner of the workspace. This allowed me to see the placement of the mask. When you look at the image, the “red area” indicates where the mask has been placed. The tricky part with masking is knowing what part of the image will be affected. In this case, the red (masked) area will be affected by the changes made in the toolbox. In other uses of masks, the red area may be the area that is unaffected. You have to learn how each masking activity works. After I was happy with the mask placement, I unchecked the “overlay” and “mask” boxes so that I could see how my edits were affecting the picture. |

| As you can see, the use of a mask created quite a dramatic difference on the background. |

This example is a very simplistic use of masking. With masks, your creativity can become unlimited.

If you’d like to learn exactly how to improve your photography through the use of masks, you may want to look into the in-depth Understanding Masking please join our Photoshop workshop